BVD-PI Virus FAQ's

What does disease due to BVD virus look like in a cow-calf herd?

One of the main problems with this virus is its name. Although BVD stands for “Bovine Viral Diarrhea”, rarely does an animal show any symptoms of diarrhea. Instead, cow-calf producers may detect one or more of the following reproductive problems in the herd:

- Poor reproductive performance/ more open cows despite good nutrition and fertile bulls;

- Decrease in overall pregnancy rate and % pregnant after the first service. This “delayed breeding” is often blamed on the AI technician, a dud bull, hot weather, or fescue when really it is a viral problem.

- Abortions (at any stage of gestation), stillbirths, neonatal deaths, and weak newborns

- Physical abnormalities (“dummy” calves that cannot suckle, eye defects, cleft palate) in newborns;

-

Calf losses due to pneumonia or scours before weaning.

It is important to realize that BVD virus in a herd may not have easily recognizable “classic signs” such as an increased number of abortions or birth defects. It may simply look like fewer mature cows pregnant at pregnancy check or finding cows open that should be calving.

How does BVD virus get into a cow-calf herd?

Research has proven that the #1 cause of BVD virus entering a herd is through the purchase of pregnant females, especially first calf heifers, without proper testing for the virus. Testing must include testing both the pregnant female for BVD and testing her calf after birth for “PI” status. All newly purchased cattle, regardless of age, should be tested for presence of the virus and isolated from the herd until results are available.

Other possible sources of the BVD virus in a cow/calf herd include introduction of PI bulls into the herd without testing for BVD, fence line contact with a PI feeder calf or a PI calf in a neighboring herd, and a calf purchased from a sale to graft on a cow may be PI. The virus may also be transmitted by blood through contaminated equipment and show cattle can carry the virus back when they return to the farm from fairs and exhibitions.

If I purchase a pregnant cow or heifer and she tests BVD negative, why would I need to test her calf at birth?

Although the pregnant cow is negative, she may be carrying a persistently infected (“PI”) calf that will test positive.

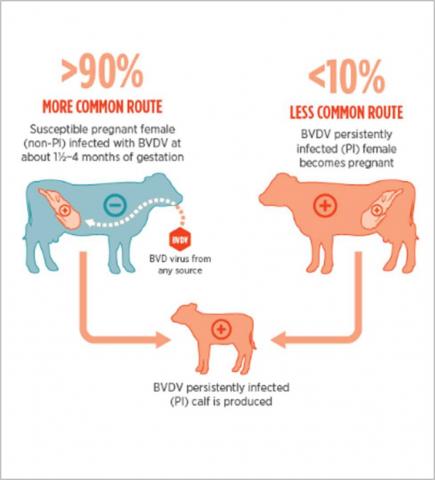

Most PIs are born to heifers who were naïve (poorly vaccinated) at the time of BVD infection. The dams that experience a short, transient infection while pregnant will be negative when tested for BVD PI but their calves, if PI, will be positive. However, a PI dam will be positive when tested for BVD and her calf will be positive, too. Bottom line: If a calf tests positive, the dam can be either positive or negative! But, if a calf tests negative, the dam can only be negative (see Figure 1). Talk to your vet if you need further clarification.

Why is it important to identify PI calves in the herd?

“PI” animals are the major reservoir for the virus and the reason it continues to exist. A BVD-PI calf is born with the BVD virus and sheds virus continuously everywhere it goes throughout its life. PI animals are the primary source of virus transmission because they shed an extremely high number of virus particles throughout their lives in feces, urine, saliva, and nasal discharge. If a PI survives to adulthood, virus is also secreted in milk, semen, uterine secretions, and aborted fetal membranes. A PI cow will always produce a PI calf. The virus is deposited in watering troughs, feed troughs, round bales of hay, cattle trailers-virtually everywhere the animal goes-and then picked up by the other cattle in the herd, either by mouth or nose. What is largely misunderstood is the effect one BVD-PI calf in the pasture can have on mature cows during breeding and early pregnancy. The most critical 30-day timeframe in a pregnancy is 60-90 days of gestation. If one PI calf is out in the pasture constantly shedding virus during breeding season, many (if not all) of the cows/heifers will be exposed to the virus during this high risk time, resulting in early embryonic deaths, delayed breeding, abortions, malformed calves, and development of the next generation of PI calves. In addition, calves born in the same group as the PI calf may have more sickness (scours, summer pneumonias) due to the immunosuppressive effects of constant virus exposure from the PI calf.

Remember, all PI animals are born as PI calves and will remain PI for life.

How are PI calves identified? Do they look different?

PI calves may appear stunted and grow poorly or may look completely normal. For example, the top bull in the 2000 Wisconsin State Fair was tested and found to be PI. Although it is often assumed PIs will die young, some survive well into adulthood and have calves or can be fed out to slaughter weight.

What is the best way to test a beef herd for PI animals?

Work with your veterinarian to come up with a plan for testing and what actions will be taken with the results. To test the herd, the following steps are recommended:

-

Test all calves at an early age- Calves should be at least 2 weeks old before taking an ear notch sample. If using a controlled breeding and calving season, test all calves after the last calf is born but before placing the bull in a breeding group in order to remove PI calves from pasture before breeding begins. Ear notches can be stored in the freezer and submitted at one time if desired.

-

If a calf is confirmed positive, then test the dam. Remember, a calf can be positive for PI but the dam will usually be negative (see Question 3 for the explanation).

-

Test any cow without a calf at her side. If pregnant, it is acceptable to wait and instead test her calf when it is born. If calf is negative, then the dam can be assumed negative and does not need to be tested.

-

Test all bulls and replacement heifers (purchased or raised).

-

Purchased Pregnant Cows-Quarantine and test purchased cow and, if negative, she can join the herd. However, bear in mind her calf could still be a PI. Test her calf when it is 2 weeks of age or older, the sooner the better.

-

Remember PIs are considered defective and there is a legal, moral and ethical obligation to either feed them out for personal consumption or euthanize and dispose of these animals without sending/returning them to commerce. Animals that test positive are not to be sold, given away or transported without approval of the State Veterinarian.

I tested all of the calves born this year in my herd and found one PI calf. The vet euthanized the PI so are my other calves (that all tested negative) normal?

Discovery of even one PI calf usually indicates big problems on a cow/calf operation. Any calf infected with BVD virus while in the uterus of the pregnant cow but did not become a PI will still not be normal. The virus uses calf cells that are essential for development of immune tissue. The virus destroys endocrine tissue and may destroy 20-80% of the thymus gland, an important driver of immune function in calves. These calves will have increased respiratory disease, poor performance, and if they reach sexual maturity, reproductive issues. Bulls infected before sexual maturity may have BVD virus persist in the testes and later produce BVD-infected semen.

How long does the BVD virus last in the environment?

The BVD virus is a “single-stranded RNA virus” which is very stable under moist and cool or cold conditions. It is not affected by freezing and can easily survive at least a week in the right environment. Its enemies are soap and water and hot and dry conditions. It can only be spread short distances through large “droplets” (especially saliva and nasal discharge) and cannot be spread by the wind. BVD virus is not contagious to humans.

If I vaccinate my herd annually against BVD, is my herd fully protected?

Unfortunately, no. Vaccines against BVD (including those with Fetal Protection claims or “FP” vaccines) will reduce the chance of creating a PI calf but protection is never 100%. Vaccines may fail due to problems with the vaccine itself, the animals, and/or management errors. The current BVD vaccines available contain BVDV 1a and BVDV2a strains. These vaccines were quite effective when strains 1a and 2a were the most prevalent types. However, the most common type of virus circulating now on farms in the US is BVDV1b so the vaccines are not as protective. Problems within the animals themselves may prevent good vaccine response. Animals that are sick when vaccinated, too stressed to respond, in poor nutritional status or too young to produce antibodies will not be protected with vaccination. A PI calf within a herd will suppress immune response from vaccine in all of the other calves it contacts. Finally, yet importantly, management errors are an all-too-common cause of vaccine failure. These may include:

-

Not giving 2 doses of killed vaccine as described on the label

-

Improper mixing of vaccine (shaking violently rather than swirling)

-

Failure to use modified live vaccine within 1 hour of mixing (VERY COMMON ERROR)

-

Inappropriate storage either before or during use of the product (must be kept cool)

-

Use of expired vaccine

-

Use of soap, detergent, or disinfectants to clean the inside of multi-dose syringes used to inject modified live vaccine (inactivates vaccine)

-

Poor timing: The immune system needs two weeks to develop a protective response from a vaccine before challenged with the virus.

Which vaccine is better, modified-live or killed? When should vaccines be given for optimal protection from BVD?

The highest risk for a bovine pregnancy is the 30-day timeframe from 60-90 days of gestation. Therefore, the goal is to maximize immunity during the first trimester of pregnancy. Mature, breeding-age cattle should be vaccinated 4-6 weeks prior to breeding with a combination viral respiratory vaccine (IBR, BVD, PI3, BRSV) with Campylobacter fetus (Vibriosis) and 5-way Leptospirosis included. Follow label directions carefully.

The question of whether to use modified live or killed vaccine is not an easy one to answer. Many popular beef magazines offer articles concerning what types of vaccines work “the best” or are “safest” according to the latest research. The truth is, there are tradeoffs when it comes to vaccine selection. Modified live vaccines (MLVs) offer better and more effective pregnancy protection but the IBR portion of the vaccine can impact conception rates if given too close to breeding season. If using timed artificial insemination (AI), experts recommend administering MLV vaccines 45 days pre-breeding in order to allow 2 estrus cycles prior to insemination. In addition, MLV vaccines can cause abortions if given to pregnant cattle without strict adherence to label directions. Killed vaccines, on the other hand, are safer but are not nearly as good at preventing fetal BVD infection. A herd with excellent biosecurity and at very low risk can err on the side of safety and use killed vaccine. However, herds that purchase animals (including bulls) or herds in close proximity to stocker cattle, unvaccinated neighboring cattle, or any other probable exposure should err on the side of efficacy and choose modified live. Another option is to administer two doses of MLV vaccine to open heifers (at weaning and a second dose 6 weeks prior to breeding) with annual revaccination using a killed vaccine. This combination stimulates excellent protection without the risk of MLVs although this protective response will diminish after several years. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, cattle herds are unique entities with different risks for disease on every farm so work with a veterinarian to choose the right vaccines for the herd.

Why are BVD-PI calves such a big problem for the stocker/backgrounder industry?

There is much concern in KY regarding the identification and subsequent movement of feeder cattle persistently infected with the Bovine Viral Diarrhea virus (or “BVD-PI” animals) into livestock sales. A BVD-PI calf is born with the BVD virus and sheds virus everywhere it goes for its entire life. When an unvaccinated or stressed feeder calf comes in contact with a BVD-PI calf, the virus is easily transmitted from the PI to the susceptible calf. The BVD virus utilizes two very effective weapons once it invades the new calf. The first attack is on the immune system where it destroys the production of disease-fighting white blood cells causing severe immunosuppression. Secondly, the virus works cooperatively with other respiratory viruses to make them more aggressive and deadly. This combination attack results in substantial respiratory disease and death loss in the stocker/backgrounder industry.

If I buy feeder calves and do not test them for PI, but I do give them two rounds of respiratory vaccine, then I am “home free” with no more worries of a respiratory outbreak, correct?

Not necessarily. The BVD virus can easily mutate or change while reproducing itself and has the ability to pick up pieces of other viruses and stick them inside its own genetic material. This can lead to rapid change (mutation) from a low virulence strain (not very “mean”) to a killer virus. If a PI animal remains in a group of calves, he continually sheds BVD virus that can mutate. Infection with this newly formed strain may result in a respiratory break after 30 days or more and can cause continued significant sickness and death loss. If a calf survives the infection, it takes an average of 14 days to clear the virus from a “transiently” infected calf but it may have effects up to 28 days or more.

Figure 1: What route does the BVD virus take in order to produce a PI calf? Over 90% of the time, it is through a PI negative dam.

| BVD PI Testing can be Confusing! |

| When testing calves for PI: |

| If calf tests positive, then test dam. The dam’s result may be either negative or positive |

| If calf tests negative, no need to test dam. The dam’s result will be negative |

| When testing cows (dams) for PI: |

| If dam tests positive for PI, her calf and every calf she has will always be positive. |

| If dam tests negative for PI, must test her calf. The calf may be either positive or negative. |